The Age of F.I.R.E.

A tryptch

Contents

Introduction

Inspirations

Hello and welcome - sit by the fire

Book One: The Forth’s Dominion (Energy)

Book Two: Trinity Hospitals (Knowledge)

Book Three: Dere Street (Movement)

_________________________________________________________

" an open-ended artistic analysis of an environment: new meanings, new poetry and further developments are always possible" -Kevin Lynch

“ If it is now recognised that people have multiple identities, then the same point can be made in relation to places... It is from this perspective that it is possible to envisage an alternative interpretation of place.” - Doreen Massey

"Today, there is a need for places rich in messages that provide a sense of belonging; most places have never been maximised" - Bob McNulty

"Finisterre, to break it down and start again" - St Etienne

________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

This site mixes the social, political, economic, intellectual and spiritual contexts of urban and community regeneration in the city of Edinburgh and the Forth river valley. This will bring together writing, field trips(critique, history and biography) with architecture, aesthetics, new chorographies, memory politics and meditations on community time. It's a bit beyond a weblog but it's interesting to try out new things...

The Critical Attitude:

The critical attitude

Strikes many people as unfruitful

That is they find the state

Impervious to their criticism

But what in this case is an unfruitful attitude

Is merely a feeble attitude

Give criticisms arms

And states can be demolished by it

Canalising rivers

Grafting a fruit tree

Educating a person

Transforming a state

These are instances of fruitful criticism

And at the same time

Instances of art

- Bertolt Brecht

_________________________________________________________________

INSPIRATIONS - Ideas, art, architecture, film, photography and music:

Thanks to:

Laurie Anderson - United States I-IV

John Latham - The Five Sisters

John Ruskin - Unto This Last

Thomas Carlyle

John Dos Passos - The U.S.A. Trilogy

Robert Smithson - The Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey

Ken Worpole - 350 Miles & Here comes the Sun

Peter Hall - Cities In Civilisation

Andreas Huyssen - Present Past; urban palimpsests and the politics of memory

Aldo Van Eyck - The playgrounds and the city

Jonathan Raban - Soft City

Will Alsop - Supercities

Curtis Mayfield - 'Back to the World', 'New World Order' and 'there's no place like America today'

Patrick Geddes - Civics as Applied Sociology

Robert Fishman - Bourgeois Utopias

Kevin Lynch - The Image of the City & What time is this place?

Thomas Schlereth - 'Cultural History and Material Culture'

Andy McDonald - CCIS Voices

Richard Sennett - Flesh and Stone

Jessie M. King - The Grey City of the North

Chris Harvie - Mending Scotland

Gerry Hassan - Dreaming City & http://www.gerryhassan.com/

Cedric Price - Potteries Thinkbelt (1965) and Fun Palace (1964)

Mike Davis - City of Quartz - excavating the future in Los Angeles

Claudio Magris - Danube

W.G. Sebald - The Rings of Saturn & Austerlitz

Tom Gallagher - Edinburgh Divided

H.V. Morton - I saw two Englands and Blue days at sea

Ben Watt - Buzzin' Fly Vols I-V and Outspoken project

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen - The Coal Coast

Massive Attack - Protection, Mezzanine, 100th Window and Heligoland

Michael Denning - The Cultural Front

The Norton Park Group - The Singing Street (1951)

Franco Bianchini - City of Quarters

Lia Ghilardi - Culture at the Centre e-book and report

Neil Smith - The new Urban Frontier - gentrification and the revanchist city

St Etienne - Finisterre (2003)

Andrew Crummy - Art the Catalyst

Helen Crummy - Let the People Sing

_____________________________________________________________________

out of the blue (Edinburgh - www.outoftheblue.org.uk)

OUT OF THE BLUE

IS: an arts and education trust based in Edinburgh

____________________________________________________________________

the Bongo club (Edinburgh)

____________________________________________________________

Alex Hamilton -

Windmills of Innerleithen

www.hamiltonashrowan.com

Cyanotypes - early Victorian 'sun pictures' or photograms

www.threshold10.com

____________________________________________________________

Fablevision Glasgow - www.fablevision.org.uk

Royston Road Parks

Trains, Weans and Mobiles - radio drama

The Adult 'A' Team - DVD

Treasures of the Royston Road - DVD

The Alien8 project - DVD

___________________________________________________________

Sustainable Rotterdam - Holland

- www.sustainablerotterdam.com

Exploring urban development and related disciplines in Rotterdam and elsewhere: sustainability, architecture, design, mobility, social issues. Reviews about exhibitions, books, sites, research and obervations

_______________________________________________________

Hello and welcome

Come in and sit down by the side of the fire

I guess you could say that for much of humanitys' time on the planet, we've lived in an age of fire.

One of the great leaps forward in human development on the planet earth was the control and use of fire. Fire always had magical properties. A gift of the gods. Sacred fire. The old myth of Prometheus, chained to his rock forevermore, all because of fire.

The bible says that God first destroyed the world with a great flood. The next time it will end in fire.

Destructive fire

Fire storms

friendly fire

God appeared to Moses in the form of fire

God cut the ten commandments using fire

The fires of love

we'll keep the home fires burning is what people say

As a child, they told me you could see pictures in the fire

Like William Blake with his fiery visions

The fires of revolution.

Fire actually was a revolution for humans

A permanent revolution

______________________________________________________________________

'Finance, raw material and control of industrial trade as its underpinning'

- Chris Harvie

The great thing about fire is how it changes its form, its colour and how it changes things.

So a few years ago, I listened to people in Edinburgh who were at a conference on urban regeneration and the development of a city-region. They were talking about the importance of FIRE and the need to keep the FIRE sector alive, I was both interested and bewildered until I realised that fire had once again changed its shape and we were talking about....

The age of F.I.R.E. - Finance, Insurance and Real Estate.

They kept talking about the importance of the F.I.R.E. sector. They kept stating the central role of finance in enabling and sustaining urban regeneration. So, I asked, surely, it's not just about the money...?

And they agreed and then they spoke about the need for sustainability, particularly energy sustainability, about the importance of the knowledge economy and the need to attract and retain financial and human capital if the age of F.I.R.E. was to be maintained.

So, I thought, Finance, insurance, real estate, all being supported by energy, knowledge and migration...

I thought, there's my story.

John Latham - The Five Sisters

________________________________________________________

BOOK ONE - THE FORTH'S DOMINION (ENERGY)

________________________________________________________

THE FORTH'S DOMINION

PLACE SENSITIVITY IN THE FORTH RIVER VALLEY

" Entering this valley

is like entering a memory

what is this valley

that speaks to me like a memory

whispering with all its branches

this november morning ? "

- Kenneth White

In the first instance, the aim is to create a picture, though not a naturalistic one, of urban and community regeneration in the city of Edinburgh and the Forth River Valley in Scotland. The city has many faces and facades. The river appears and disappears throughout the work. It follows twists and turns, loops, flows underground on occasions. So, this work will not follow a linear path either.

- Patrick Geddes - the Valley Section

Also, there are certain images that will re-occur again and again. These are quite simple images relating to oil and water, coal, fire, the wind and tide, urban buildings, clocks, turbines and the wheel of the stars in the northern sky.

To aid this process, I will use the musical concept of the motif (from classical music) or phrase (from jazz) or version (from reggae) as a tool. This will often involve the repetition of a theme but will then follow a different trajectory of investigation and analysis. This means that I’ll strike certain key notes again and again. So, you will meet the same places, the same images again and again, but from a slightly different perspective.

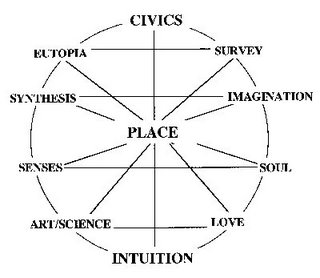

In terms of structuring this riverbook part of the tryptch, I’ve adopted an approach that is constructed of layers. In this approach, I follow the examples of the study of place to be found in the writings of Kevin Lynch (1960), Richard Sennett (2003), Jonathan Raban (1972), Doreen Massey (1998) and Patrick Geddes (1915).

In the work of these writers, places are ‘texts’ that can be read and re-read and which particularly repay close reading. Each of these writers has stressed the ‘layering’ of places via using memory, architectural, archaeological or geological terms, emphasising that past, present and future exist together - what the Chinese poet Yang Lian calls 'the archaeology of now'

Memory politics

'So beyond working and playing comes remembering'

- Patrick Geddes

The rationale underlying this approach is that the process of regeneration and change occurs for both human generations and places and that this process leaves marks and traces. The presence of change is registered in both catastrophic (the movements of the earth in geological terms, the traces of water on the faces of rocks or the demolition of housing, industrial closure of mines, successful and unsuccessful collective actions by communities) and mundane terms that co-exist.

It is easy to find the evidence of catastrophic events. They can be found in newspaper headlines, empty buildings and the silencing term ‘brownfield’ that wipes clean the industrial past. Evidence can also be found in oral history and cultural projects of places all over Edinburgh although these are rarely catalogued or archived in such a way as to aid analysis and research. The mundane is more difficult to find. You need the techniques and approaches of salvage anthropology. All too often its effects are found via attention to detail, by a slight shift in perspective, to paying attention to traces, the writing of water on the face of rocks to forgotten languages, symbols and somatic traces.

This is also an interactive piece of work. It’s not just designed to be read from your computer screen. Inspired by Robert Smithson and 'The Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey '(1967) and the Norton Park group's work on city lore, there are five trails to follow.

The wind, the wind, the wind blows high

Snow comes falling from the sky.

Margaret Thomson says she’ll die

For the want of the Golden City

Wolfgang Suschitzky Children of the City

_________________________________________________________

PLACE – IN THE ARMS OF THE SEA

“Now, what I want is, Facts.. In this life, we want nothing but Facts, sir; nothing but Facts!”

- Patrick Geddes - a holistic approach

THE ENERGY VALLEY

The River Forth is a tidal river, it mixes fresh and salt water. It’s also a long river, that has helped to create a big valley running a 100 km from source to the mouth of the river. The very name mixes past and present. The word ‘firth’ is an old norse word. It means ‘arm of the sea’. Many of the settlements are located around tributary rivers that flow into the Forth. A lot of the place names have the pre-fix 'Aber' like Aberlady. 'Aber' is a Pictish word. It means 'mouth'.

How many arms has the sea?

The river has always been central to the human development of this part of the earth. Even now, the oil, agro-chemicals and pharmaceutical industries located on Firth of Forth contributes more than 50% of the Gross National Product (GNP) of Scotland.

But the river is a haven for other animal and plant life because it is a transition zone between fresh and salt water. It’s a threshold space, a door that opens both ways. It provides a range of habitats that support a huge diversity of life from anaerobic bacteria, to birds, humans and whales.

In 1929, a Member of Parliament, John Burns stated that:

‘The St Lawrence is mere water. The Missouri muddy water. The Thames is liquid history.’

I'm not sure if you can just say that about the Thames alone. That's very London-centric. I've nothing against London but I liked the idea.

History as liquid.

History in the liquid state.

Fluid, mixed.

Time as liquid

Time in the liquid state

Fluid, mixed

"Time is the substance I am made of.

Time is a river that carries me away,

but I am the river "

_____________________________________________

THE ENERGY REVOLUTION

Let's start with energy

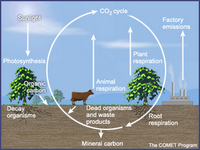

The environmental historian John McNeil argues that there was an ‘energy revolution’ as much as an ‘industrial revolution’ as Europeans and North Americans gained access to huge reserves of photochemical energy locked within coal seams that in turn powered their steam and oil engines.

Something new under the sun - John McNeil

The industrial development of these seams and the energy they produced materially altered the energy use, transportation systems, the standards of living and landscapes of Europeans and North Americans.

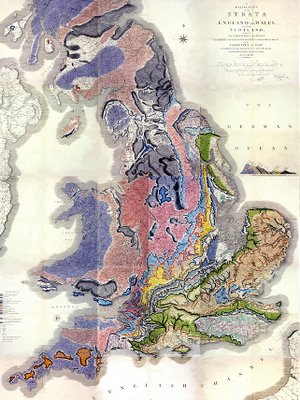

The city of Edinburgh sits in the middle of giant coal seam that stretches across the central belt of Scotland.

William Smith - Geological map 1815

________________________________________________________________

What is the aesthetic of the energy revolution?

Did the energy revolution have an aesthetic?

Can you find it in Edinburgh?

The coal energy period certainly had an aesthetic. Giant cities, steam, smoke, iron and stone. One of the nicknames for Edinburgh was 'Auld Reekie' - literally old smokey

There were ‘Boom towns’ that grew rapidly, named ‘Coketown’ by McNeil in reference to the town in Charles Dickens 1854 novel ‘Hard Times’. The heroic figure was the engineer, the ironmaster, the industrialist. It also produced a vision of the opposite - the Garden City of Ebenezer Howard and the New Towns of the post second world war period.

Ebenezer Howard - Garden Cities of the future

" The real breakthrough of shipbuilding and engineering in the 19th century was the creation of the delivery mechanisms for the coal - machinery, railways, ships - on which industrialisation depended until world war 2" - Chris Harvie

The coal energy period also produced materials (not only coal but also slag heaps such as the 'Five Sisters' in West Lothian), wealth, misery and an industrialised landscape on a scale that shocked contemporary observers such as Dickens and Zola.

John Latham - The Five Sisters 1974

At the same time, the boom led to bust as many of the coal seams proved narrow or uneconomic to mine in the longer term. McNeil states that the coal had a dual use both for fuel and in the production of initially iron and steel and later for the generation of electricity. This was followed by other industrial-chemical products for both growth and export such as motorcars (developed in factories that are christened ‘Motown’ by McNeil) cement, chemical products etc.

But, you know, the lifetime of the coal energy period was not long. McNeil states that the coal energy fuel complex was both displaced and replaced in the second half of the 20th century by oil, gas and nuclear fuels.

The oil energy period again materially altered the energy use, transportation systems, the standards of living and landscapes of Europeans and North Americans. The oil energy period also had an aesthetic. This was the aesthetic of the highway and the car, concrete, steel and glass. Frank Lloyd Wright may have been the prophet of this age. Broadacres was his vision and his gospel. But he wasn't the builder. The builders were Norman Bel Geddes and Victor Gruen.

Norman Bel Geddes' Futurama exhibit at the 1939 New York's World Fair and his book 'Magic Motorways' set the blueprint.

Victor Gruen built his Southdale shopping mall in Edina, Minnesota in 1956.

Laurie Anderson spoke in ‘Big Science’ of:

“Golden cities.

Golden towns

Golden cities.

Golden towns

And long cars in long lines

and great big signs

and they all say:

Hallelujah.

Yodellayheehoo

Every man for himself.”

Edinburgh got lucky again as the main processing plant for oil and gas from the North Sea fields sit on the Forth. Part of the reason the F.I.R.E. sector is so important is because of oil money flowing around.

The nuclear energy period. Well, that was an age of fire. It also had an aesthetic - a Cold War pastoral, security, hidden silos and submarines. William Hoskins, in his work 'The making of the English Landscape', launched a jeremiad at the devastation of the countryside by scientists, the military and politicians. A landscape dominated by 'the obscene shape of the atom-bomber, laying a trail like a filthy slug upon Constable's and Gainsborough's sky. The Nissen hut, the 'pre-fab', and the 'electric fence’, the high barbed wire around some unmentionable devilment'.

- Cold War Pastoral - John Kippin

Well, that is one way of looking at landscape and you can find it near Edinburgh at Rosyth, in the giant radar listening posts shaped like golf balls that are dotted around the landscape, or you can visit it at Torness nuclear power station.

The landscape of Edinburgh and the Forth river valley is presently littered with examples of ‘former industrial areas’, ‘new towns’, 'garden cities' (such as Rosyth - the garden city settlement that became the base for the nuclear submarines and now the European ferries) oil depots, bunkers, airfields and secret underground communication centres from the previous phases of the energy revolution.

Rosyth Garden City

____________________________________________________________

You see, the ground below our feet in Edinburgh and in the Forth river valley contains the abandoned legacy infrastructure of mining tunnels and workings, the land is crossed with motorways and shopping malls, the face of the sea and the arc of the sky contain sea-routes for the transport of oil and gas and flight paths for those that know.

The 'brownfields', the 'backlands' and the former industrial areas - they have stories to tell

These areas have impacts and questions for urban regeneration.

" You look north, and see a huge tract of birch waving over the graveyard of scores of furnaces and foundries, collieries and power stations, hundreds of miles of railway and a vanished revolution" - Chris Harvie

Now we're in the 21st century, we're moving into the renewable energy period. Arthur C. Clarke noted in 1973 at the time of the first ‘oil shock’, ‘the age of cheap energy is over. The age of free energy is still fifty years away’.

We sit around the fire, telling stories

asking questions

What are the stories of the energy periods?

What are the stories of coal and oil?

What are the stories of nuclear power?

What are the stories of renewable power?

Was it really so cheap?

In 1953, the Chinese communist Zhou Enlai was asked his opinion of the significance of the French Revolution of 1789. He thought for a while then replied with a shrug, “It’s too early to tell”

“If we want to improve the condition of our planet, we must realise it is not what we do that matters, but the questions we ask that lead to our actions” - Cedric Price

Or is it too early to tell?

_____________________________________________________

DARK ENERGY

THE COAL STORY - PART 1

"What one sees from the air, then, are not merely attractive patterns and forms but great metabolic scaffoldings of material transformation, transmission, production and consumption. The country is an enormous working quarry, an operational network of exchange and mobility. – James Corner

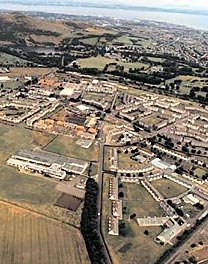

Craigmillar is a conurbation of local authority housing estates built after 1930 in a period of industrial re-location and central city slum clearance. It is located on the south east of the city of Edinburgh. It is an area that has steadily been positioned from the late 1950’s as existing on the periphery, both geographically and economically. But it was not always peripheral.

Coal has been dug from the ground in the Craigmillar area since the Middle Ages under the supervision of the monastic estates for the purposes of both heating and in the production of sea-salt on the nearby tidal estuary of the Firth of Forth at Prestonpans. At night, you could see the fires of the salt pans. This coal and salt was sent to the Netherlands, Scandinavia, the Baltic countries and England.

The Craigmillar housing estate was built on the land around and incorporating the 19th century mining and mill villages of Newcraighall, the Jewel and Niddrie. These are adjacent to the other south Edinburgh mining village of Gilmerton and nearby county of Midlothian with its numerous pit villages that were all under the ownership of the Kerr -Ancram family as the Lords of Lothian.

Let us the strike the keynote - Coketown

Edinburgh - a capital of coal and oil

The early residents extracted what existed beneath their feet. The geology of the central belt of Scotland comprises a significant coalfield that was laid down in the Carboniferous Period 350 million years ago. This includes oil-bearing strata in West Lothian from where the first commercial extraction of oil from coal took place via the chemical process pioneered by the petroleum-chemist James Young in the mid 19th century. This coalfield is in turn part of much larger coal and oil-bearing strata that stretch across Europe and into the North Sea.

This was once the tropics

The development of this European coalfield was part of a general and rapid expansion of the mining industry in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The mining of extensive seams of fossil fuels for energy such as coal on an industrial scale produced the ‘Coketown cluster’ identified by the environmental historian John McNeil (McNeil 2001, p306). This is named after the fictional town in Dickens’ 1854 novel ‘Hard Times’.

Coketown and the Coal rush

These communities were ‘boom towns’ that grew rapidly. They also produced materials, wealth, and misery on a scale that shocked contemporary observers such as Dickens and Zola. At the same time, the boom led to bust as many of the coal seams proved narrow or uneconomic to mine in the longer term. The landscape of Europe is littered with examples of ‘ghost towns’ connected to the mining of both coal and lead that remind us that the decline of former industrial communities has a long history.

a cycle of boom and bust

Welcome to the Energy revolution

The Coketown clusters produced an ‘energy revolution’ as much as an ‘industrial revolution’ as Europeans and North Americans gained access to huge reserves of photochemical energy locked within coal seams that in turn powered their steam and oil engines. The development of these clusters and the energy they produced materially altered the energy use and standards of living and wealth of European and North Americans on an exponential scale.

Grangemouth

McNeil states that Coketown produced coal not only for fuel but also for the production of initially iron and steel and later for electricity and other industrial-chemical products for both growth and export such as motorcars (developed in factories that are christened Motown by McNeil) cement, chemical products etc. These products make up the GNP or the wealth of nations.

The lifetime of the cluster was not long. McNeil states that the Coketown fuel complex was both displaced and replaced in the second half of the 20th century by oil, gas and nuclear -based fuel forms. This process happened in the United States, Japan and Western Europe throughout the second half of the 20th century.

________________________________________________________

NEWSREEL

NEWCRAIGHALL STRIKES GOLD -'BLACK GOLD!!

In 1897 two incline shafts were sunk at the west side of Newcraighall village. It was officially named Newcraighall Colliery but when the miners were told that it had enough coal to last THREE HUNDRED YEARS AND MORE, they were jubilant. They nick-named it THE KLONDYKE as this coincided with the Gold Rush in the Yukon of West Canada to which many Scots had gone.

Miners were convinced that from that day on there would be work in plenty. Those rich coal seams would surly mean fair wages, vast improved working conditions, with safety measures being introduced. Now at last, they would be able to give their children the things they never had, a decent home, adequate and healthy food and decent clothing.

Now that the Elementary Education Act of 1872 made primary education compulsory for all, they saw their children getting a good education with years of steady work to look forward to when they left school. Sons who, because of unemployment had been forced to leave the village, could now return. The Klondyke was going to provide work for all and more! And so they dreamed!

That year the village received another boost. The Dalrymple family presented it with the gift of a new Bowling Green. This started as a small green near the village, but later transferred to the present site beside the old Newhailes Station.

In 1900 the school was burned and education was severely affected.

THE 1900's

As the village went into the 20th century a large quantity of cannel coal was being extracted at the Klondyke for use in the manufacture of gas. but when incandescent mantles were introduced, more common types of coal could be used. The bottom dropped out of the market. By then the most important seams at Klondyke (or Niddry as it was officially called) were, Parrot Stairhead. Corby Craigie. North Green.

By 1902 workings in the incline at Klondyke reached depth of 460 fathoms. It was one of the deepest mines worked in Scotland at that time (approximately 2760 feet) It was to reach 16 miles in length, 130 fathoms deep and run for 1) miles under the River Forth, This the miners called the Sea Dook).

1968 - KLONDYKE PIT CLOSED..

Bitterly contested by the miners, their Union and the local Labour Party. who though they failed to stop the closure, fought to get the best redundancy payments possible. The younger miners were offered jobs elsewhere, but many older miners never worked again.

In true mining tradition nothing was wasted. the coal- bing was sold to the Regional Council and used as a foundation for the building of a new Motor-way skirting the village. This was opened in 1986.

Beside it on the cleared bing site, the INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, the community has so long fought for, was last being built. Or so the community thought. On it now is a shopping development, Kinaird Park.

197l - 27th November, the Pit winding gear was dismantled and transferred to the Prestongrange Mining Museum. Verbal assurance was given by David Spence founder member of the Museum and ex-Manager of the Klondyke that they will be returned to Newcraighall if the villagers ever so desire.

________________________________________________________

EDINBURGH - CAPITAL OF COAL

With the decline of the Coketown cluster came a focus on regeneration of the places. If we apply McNeil’s replacement analysis to the Scottish coalfield a perspective emerges that appears to support his thesis. If we take Craigmillar in Edinburgh as the centre, then within a fifty mile radius (linked by rail) from this epicentre (in the period 1930-1990) could be found not only numerous pit villages in East Lothian, Fife, Midlothian, West Lothian, Ayrshire and Lanarkshire, but also three major power stations at Longannet (Fife), Portobello (Edinburgh) and Cockenzie (East Lothian). In the same period the ports of the North and South sides of the Forth (Alloa, Boness and Leith) sent coal for internal use to nd London and for export to Europe and the British Empire. In Lanarkshire, the former Ravenscraig steel works (connected by rail to Craigmillar) produced steel for both internal (UK) use and imperial export. At Bathgate, (West Lothian) and Linwood, (Renfrewshire) were sited car production factories.

It can be seen that the central belt of Scotland had its own Coketown-Motown cluster.

This was displaced and replaced in the latter part of the 20th century by oil (at Grangemouth in West Lothian), gas (at Mossmorran in Fife) and nuclear (Torness in East Lothian) all within the same fifty-mile radius.

Legacy Infrastructure: Four impacts of Coketown

Big smoke

Firstly, there was the major impact on the surrounding environment in terms of pollution of air, water and land. The by-products of the mining industry fed into each. This resulted in damage to cities, people and animals. The damage caused began to be addressed by public campaigning (by communities, the media and trade unions) and resultant legislation from the 1960s onwards with regard to the pollution of air and watercourses and industrially related diseases. The fatal Aberfan disaster of 1966 (where a slag heap collapsed and buried a primary school) encouraged the clean up of some of the slag or waste heaps in the UK but land reclamation and the removal of industrial by-products and toxic waste along with the problem of subsidence remains a major ongoing project across Europe.

Big Jobs

Secondly, the impact on the mining industry as an employer. The mining industry was the main employment ‘engine’ of the community and the main employer of the local male working class. The majority of the males arriving in Craigmillar in the 1930s from the central Edinburgh slums would find work in the newly expanding mining industry of the Lothians. The size and expansion of this industry in maintaining the energy revolution should be critically understood. In the so-called ‘Klondyke’ pit alone in the Craigmillar area, there were three hundred years worth of reserves. Discovered in 1897, at the same time as the famous goldfield in Yukon, Canada, it came fully on-stream in the 1930s. It closed in 1968. Today, on the site of the 'golden coal mine', there is a McDonalds. The sign of the Golden M.

The development of ‘super-pit’ such as nearby Bilston Glen in the late 1950s also indicated the size of coal seams known as the ‘Hirst seam’ and the economic importance of areas such as this to policy makers across Western and Eastern Europe. With the replacement of coal as the main energy source and the break-up of the Motown cluster male employment collapsed.

Big Welfare

The third impact is on the relationship between producer communities and consumer communities. The majority of mining communities in the UK and in Europe lie out with city centres and are rural but with rail and road links to urban-based production facilities e.g. the Sheffield steel complex and the South Yorkshire mines or the cities of Duisberg, Essen and Koln and steel complex owned by Kruups and Thyssen that was fed by Ruhr coalfield in Germany. The replacement of the mining industry meant that these producer communities lost their primary reason for existence. The Objective 1, 2, 3 and European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) programmes address this problem by seeking to build replacement infrastructure and encourage investment.

Big Questions

The fourth impact was on people. Coalfield communities across Europe (or former coalfield communities following the Europe wide collapse of the industry from the period 1960-2000) exhibit particular features associated with both rapid industrialisation and de-industrialisation e.g. high and sustained levels of male employment followed by un-employment, high levels of industrially related diseases, environmental despoliation and pollution, low levels of educational attainment, drug use, family breakdown and de-population. These have been well documented in the UK by the Coalfield Communities Campaign, the researcher Royce Turner (2000), Grainger et al (2002) and the Coal Fields Task Force Report (1998). Whilst the coalfield areas may broadly share these features with deprived inner city areas across Europe that were dependent on trade and the export of fossil fuels, they differ from these by their rural nature, the concentration of features and intensity. Again the Objective 1, 2, 3 and European Social Fund programmes have addressed this via education and training programmes.

As can be seen there were both major benefits and unforeseen consequences of the Coketown complex in its boom period. Its aftermath in terms of physical regeneration of the city of Edinburgh will be explored in the next instalment. It will also explore human regeneration initiatives.

" We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time "

_________________________________________________________

TRAIL 1: NEW CITY CENTRES

________________________________________________________

POETRY OF PLACE – F.I.R.E.

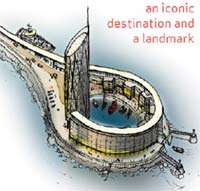

Waterfront

A new city by the sea.

It's already happening.

Western Harbour.

Granton Harbour.

Ocean Terminal.

Waterfront Plaza.

Conran and Ove Arup

Edinburgh Harbour.

Platinum Point.

Ocean Terminal.

Forthside.co.uk

It's already happening.

______________________________________________________

FRESH AIR NIGHT AND DAY AND LIVE OUT OF DOORS AS MUCH AS YOU CAN:

- Janet Smith - Liquid Assets. The front cover of the book and a case study is dedicated to the Portobello Open Air Pool or 'Water Stadium'

FROM MORALISM TO PLEASURE

Ken Worpole:

The city lido was one of the great innovations of the period in architectural history when politics and design (and a pronounced sense of the public good) came together. Early 20th-century modernism – especially in the Netherlands and Scandinavia – developed and espoused a whole series of new building types principally designed in the interests of public health and well-being: kindergarten, open-air schools, sanatoria, health centres and clinics with their own gymnasia, sports parks, lidos. This was the moment of "the social-democratic sublime".

Fresh air, sunshine, and opportunities for outdoor play and recreation were the driving principles at work, and of all these new building types, it was the lido which came to represent the pinnacle of the new culture.

Most lidos created in Britain in the 1930s actually grew out of public-works programmes for the unemployed, and turned public duty into public pleasure. They were a far cry from the previous style of municipal baths, which often had segregated areas of the pool for men and women, and were organised and managed with factory discipline. Lidos represented a triumph of the stylish and the carefree with their sensuous lines and curves and the use of cool whites and blues in their materials and decor.

This really was sex in the city. The cult of the Cote D'Azur was brought to Mersey, Manchester and Mile End.

THE PLEASURE GARDENS, OPEN AIR POOLS AND PLAYGROUNDS

The lost pleasure garden that was Marine Gardens

The Pool Association

The lost open air swimming pools:

Portobello swimming pool

North Berwick pool

Dunbar pool

Port Seton pool

The remains of a Victorian pool at North Berwick

___________________________________________________

Play, Playgrounds and City Lore

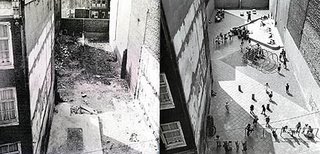

Aldo Van Eyck - the playgrounds and the city - a different approach to urban design, regeneration and a focus on non-corporate users. He worked from 1947 to 1974 designing playgrounds across Amsterdam.

Aldo Van Eyck - drawing for playground in Zeedijk, Holland

Playground - before and after

________________________________________________________

- Patrick Geddes - a thinking machine

City lore and the Norton Park Group

James Ritchie (1908-1998) was a maths and science teacher at Norton Park School, Edinburgh. He began documenting his pupils’ play traditions from the 1950s. He and his collaborators in the Norton Park Group developed the pioneering film, The Singing Street (1951), featuring the children’s demonstrations of their games and songs. He also produced two books The Singing Street (1964) and The Golden City (1965). The film contains a huge range of children’s songs, games, beliefs, customs, football chants and graffiti. The books contains a host of vivid examples of children’s lore, language and games in the city.

Still from 'The Singing Street'

The city of Edinburgh is selling off most of its playgrounds and sports grounds for property development

No blue plaques, no statues just memories and micro monuments.

http://www.playedinbritain.co.uk/books/lidos.html

http://www.citylore.org/

____________________________________________________

POETRY OF PLACE 2 – THE GREAT F.I.R.E. OF CHICAGO

This is a world-wide phenomenon

cabrini green

cabrini green is also home to a strong community of african

cabrini green is being demolished and its residents dispersed

cabrini green is chicago's cabrini

cabrini green is chicago's

cabrini green is also home to a strong community of african

cabrini green is being demolished and its residents dispersed

cabrini green is not just yuks

cabrini green is infamous as a housing project that you don't want to visit on any kind of official business

cabrini green is a housing development built in the 1940's

cabrini green is said to have the highest concentration of police in the nation

cabrini green is comprised of high

cabrini green is in fact very much a new urbanist project

cabrini green is sitting on top of some very valuable dirt; and developers

cabrini green is an organization that affords ministry opportunities

cabrini green is in an area in the process of being gentrified

cabrini green is an unexpected touch

cabrini green is under the shadow of the wrecking ball

cabrini green is a lyrically intense band with an intelligent pop sensibilty

cabrini green is a telling

cabrini green is on the phone and i am afraid to answer it's call having seen that prison

cabrini green is one of nineteen "residential communities" that are owned and managed by the chicago housing authority

cabrini green is under attack

cabrini green is a unique case

cabrini green is home to a strong community of african

cabrini green is among your most high

cabrini green is the high

cabrini green is known as 'the projects' and is actually the place where the nightmarish tale takes place in the movie

cabrini green is being slowly torn down

cabrini green is perhaps the most obvious example

cabrini green is violent and evilly funny

cabrini green is also a good example of the relationship between poverty and violence

cabrini green is the most valuable piece of property in the city of chicago; the value of the land henry horner homes is on ? right next to the united center

cabrini green is a public housing project in chicago

cabrini green is where she has decided to settle

cabrini green is this side of hell

cabrini green is no more

cabrini green is pregnant song

cabrini green is almost no longer

cabrini green is the community within the city of chicago that the chicago fellowship of friends calls home

cabrini green is in the process of being dismantled

cabrini green is the site of a social experiment in scattered site housing

cabrini green is a "war zone" ballad

cabrini green is legendary

cabrini green is a good idea here or not

cabrini green is both frightening and frightful

cabrini green is someone's neighborhood

cabrini green is one of the worst housing projects in the world

cabrini green is now condos and the area by

cabrini green is the semiotic space

cabrini green is violent

cabrini green is 99% african

cabrini green is a target for gentrification

cabrini green is made up of three separate developments

cabrini green is world famous

cabrini green is also the projects where the movie/myth of candyman began

cabrini green is now

http://www.viewfromtheground.com/archive/2005/07/restoring-the-view.html

________________________________________________

DARK ENERGY : THE AFTERMATH

THE COAL STORY - PART 2

Mining is a good way to pioneer a territory, but a bad way to hold it"

- Jonas Dahlberg "Invisible Cities"

Craigmillar in the Forth Valley

Craigmillar is a conurbation of local authority housing estates built after 1930 in a period of industrial re-location and central city slum clearance and located on the south east of the city of Edinburgh. It is an area that has steadily been positioned from the late 1950's as existing on the periphery, both geographically and economically. As Edinburgh expanded in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, it did so by incorporating outlying villages (including those in the north, east and west) into the city jurisdiction. This is quite in line with processes of urban growth in other parts of the UK and beyond. Craigmillar and Gilmerton were originally villages two and three miles to the south of the historic core of the city of Edinburgh.

What is unusual is that Edinburgh (a national capital) incorporated in the early decades of the 20th century fully-fledged industrial mining communities with their own folkways, identity and perspectives on life. This development is somewhat at odds with the development of most cities in the UK and most mining communities across Europe. It is unusual for a national capital in Europe to have a coketown cluster within its city boundaries.

If we approach Craigmillar from the perspective of an urban coalfield community closely connected to a major urban port then a great deal of the roots of social deprivation therein can be understood. The work of Eduardo Galleano on the 'boom and bust' nature of river valley cities in capitalist development is particularly constructive (albeit from a Latin American perspective) in this respect. Craigmillar demonstrates all the features of a one-time coalfield community boomtown. It sent its product across the globe via rail links to a major river valley port in Leith. It also demonstrates the features of a coalfield community in decline in terms of deprivation. The area saw significant employment growth in the period 1890-1960 as people came to the area for work.

The area suffered decline from the mid 1960s as the Jewel, Klondyke and Newcraighall pits all closed. The aftermath of the miners strike of 1984-85 saw the closure of the Bilston Glen 'super-pit' just twenty years after it opened. In the period 1965-1985 Craigmillar lost 10,000 male jobs.

site of Klondyke mine 1965

By 1990 the area had become a focus for regeneration. Following various stops and starts, the architect Piers Gough was approached by Edinburgh City Council to develop a regeneration Master plan in 1998. It is notable that the Craigmillar Master plan " A New Beginning" (2000) does not mention this industrial background at all but addresses the social problems directly. This is not surprising since the main physical evidence of the mining industry (such as winding gear, waste heaps, rail lines and coal docks) had been demolished, abandoned and/or grassed over long before the arrival of Piers Gough and his team of regeneration consultants. The limited remaining evidence of the industrial past on the surface in the Craigmillar and Newcraighall mining neighbourhoods is to be found in the housing stock from the turn of the century 'the miner's row'.

Instead, the master plan presented its vision for the area as a 'new beginning', with the provision of new houses, employment and amenities. The plan envisages the destruction and demolition of the majority of the housing stock from the 1930s. These are to be replaced with a blend of social and private housing (with private homes at prices upwards of £250,000 adjacent to Craigmillar Castle - Edinburgh's other, less famous but equally historic castle) with better transport links to the city centre and more shops.

It can be argued that this Master plan is an example of 'top down' planning in that it was never open to public competition (unlike the new Scottish Parliament building of the same period) nor were the changes envisaged ever voted upon by the public of Edinburgh or the residents of Craigmillar. Lastly, it is highly selective in what is included and what is excluded in this case the recent industrial and social past of the area.

Without communities such as Craigmillar, Gilmerton or their counterparts in Fife, East and West Lothian, the mining industry and the vital fossil fuel it supplied for industrial/social growth, Edinburgh (let alone Craigmillar), would not have grown. The heavy industrial past and the role of fossil fuel extraction in powering urban development is not acknowledged in the Master plan and remains to be acknowledged and written by planners and developers. This is because the past will not go away.

As noted above, a key feature of the mining industry is in its environmental impact. The most noticeable are the surface based slag heaps of industrial waste. Although the red-shale coal slag heaps or "bings" litter the landscape of West Lothian (resembling the arroyos, sierras and canyons of the south western USA), the ones of Craigmillar have long been removed.

_____________________________________________________

THE COAL COAST

Book and Photo by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen

"I am for the art of slag and black coal." - Claes Oldenburg 1961

Sirkka-lisa Konttinen produced a stunning series of photographs of the Durham coal coast in her book 'The Coal Coast'. The coal industry in the area has gone but the deep mines, that ran below the surface of the North Sea, throw up amazing industrial flotsam onto the beaches of the 'Heritage Coast'.

Beneath the surface of southeast Edinburgh, there are two significant problems. The first is geological and hydrological in nature. The mineshafts are deep and the coal faces run right throughout the southeastern edge of the city and out beneath the Firth of Forth. When the mines were closed, the drainage pumps were shut down and the mines filled with water. This water is interchanging with naturally occurring subterranean water -courses and flowing into surface watercourses. As a result the water of the Firth of Forth is full of industrial spoil (with lead and cadmium primarily present) from the Lothian mining industry, two decades after its closure. This is hindering a major £500 million regeneration project for the south shore of the Forth 'Edinburgh's Waterfront' (Forth Estuary Forum 2000).

The second problem is related to subsidence. In the last five years the southeastern edge of Edinburgh (of which Craigmillar is a part) has witnessed the major expansion of the so-called 'south east wedge' with the largest post war investment (via a Public Finance Initiative project) by the NHS in Scotland in the location of the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

As a result of the regeneration of the area the monetary values of former mining, industrial and agricultural land has increased significantly. This hospital led regeneration intervention, (with the assistance of Edinburgh Development Initiative, EDI- the city of Edinburgh councils' property development company), has led to waves of further major investment in road improvements, housing, amenities, a medical/biotechnology park for the University of Edinburgh and retail parks.

These are close to the city by-pass and the main motorway routes to the south, north and west. Craigmillar sits on very valuable dirt in more ways than one. All of this is being built above what was a major mining complex and there are already indications of problems. In October 2001, residential homes built in the early 1990s in Ferniehill (between Craigmillar and Gilmerton) collapsed into the ground. Luckily, no one was severely injured. Surveys by structural engineers employed by the City of Edinburgh Council discovered that the houses had been built on top of disused mining shafts from the late 19th century. De-regulation of planning consent and land valuation were blamed for allowing the houses to be built in the first place. Many of the residents have had to be re-located. The nature of the industrial scarring of the subterranean environment of the city is still to be discovered and addressed by land planners and also property developers. As we see above, if they do not so, then the past will literally swallow them and their investments up.

__________________________________________________________

DARK ENERGY: AESTHETICS OF THE COAL AGE

THE COAL STORY - PART THREE

"And this long narrow land is full of possibility? " - Deacon Blue

Craigmillar is a conurbation of local authority housing estates built after 1930 in a period of industrial re-location and central city slum clearance and located on the south east of the city of Edinburgh. It is an area that has steadily been positioned from the late 1950’s as existing on the periphery, both geographically and economically.

In 2000, the City of Edinburgh Council unveiled a new master plan for the regeneration of Craigmillar (City of Edinburgh Council 2000). The area has suffered from significant levels of poverty and disadvantage over the last forty years. This master plan involved the destruction and demolition of the majority of the housing stock. The master plan presented its vision for the area as a ‘new beginning’, with the provision of new houses, a shopping centre, employment and amenities.

This chapter will explore the area of Craigmillar in more depth and will re-visit earlier parts of the book. There will be a focus on key areas that the master plan did not address. These are the social and cultural history of the people of the area. The role of local people in consistently presenting their version of their experiences of ‘Coketown’ and in formulating an alternative vision of regeneration that goes beyond the replacement of the built environment will be emphasised. This alternative vision of regeneration will, I believe, strike a chord in many other areas of the UK and Europe that are also undergoing regeneration. It also links the cultural planning approach with that of community development.

Site of Klondyke mine 2005

In this chapter I have drawn upon oral history and reminiscence used by community development practitioners to explore the social and cultural history of the area. In addition to this, I have also taken a cultural planning approach and studied the original buildings, art works and cultural facilities of the area themselves as significant cultural texts that can be critically decoded and used for positive and socially progressives purposes by planners, academics, artists and community activists.

The majority of houses in the area were built after 1930 in a period of slum clearance and industrial re-location from central Edinburgh. Not only houses were built. There were also schools and workplaces.

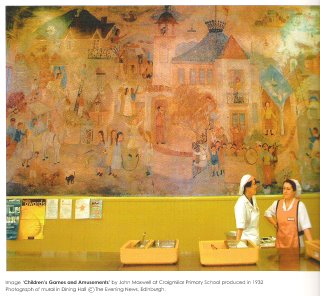

In Craigmillar primary school there is a wall mural painted by the Scottish artist John Maxwell in 1934. The wall mural focuses on and celebrates open space and sunshine. In doing so it welcomes the building of the estate as a release from the slums of central Edinburgh for the residents, and particularly the children who were both the pupils of the school and the consumers of the fresh air and sunshine.

John Maxwell - Children's games and amusements (1934)

In both time period, subject, choice and use of imagery, the wall mural is an expression of much larger global social and artistic discourses that Ken Worpole identifies in his text, ‘Here Comes the Sun’ (2000). This focuses on the expression of these discourses in the built form via architecture in cities and housing estates around the UK and Europe in the inter war period.

The imagery of the mural originated as a response to social problems and tensions of the period. These ranged from social pathologies such as the real fear of tuberculosis and defences against the disease, to both national and local social/industrial unrest (as documented in Gallagher (1986), to utopian desires expressed via the political commitments to build new ‘homes fit for heroes’ following the end of World War 1.

The imagery of the mural also focuses on what we now would term ‘quality of life’. This is expressed not only as access to fresh air and sun but also a sense of freedom and a desire to live an untroubled life. This would be particularly pertinent in the period following ‘the war to end all wars’, in the boundaries of the Coketown clusters and as some of the rewards of the energy revolution.

As Worpole argues, this desire was given both a political expression (the rise and coming to power of social democratic parties) and a physical aesthetic expression via both the painted murals and the modern architecture of the buildings that housed them. It can be argued that what Worpole stresses the oppositional elements of this desire for sunlight and health, in short, what it was a reaction against. By developing a greater understanding of the industrial history of an area: not only the polluting conditions but also the energy revolution, the material wealth and the global connections it produced, it is possible to gain a clearer insight into the drives behind these desires.

Like other housing estates of the period throughout the UK and Europe, Craigmillar has a number of modern movement buildings that in their form, styling, colours and use of materials spoke of connections to an ‘international modern world’. In Craigmillar these buildings were the Rio cinema (now demolished following a fire)

and the Niddrie Marischal secondary school building which Edinburgh architect Malcolm Fraser describes as ‘a bravura combination of international moderne with Art Deco ” (2000)

Whilst the Maxwell mural focuses on the celebratory features of the new estates, many other aspects were left out of the picture. Some provided a counterpoint to the ideologies of living on fresh air and sunshine alone. For example, one of the original residents, Helen Crummy (1992 pp 25-34) draws attention to how it felt to actually live there as a child, in the Great Depression of the 1930s when unemployment in the coal industry was high in an estate with no access to amenities and basic services such as a doctor or playgrounds. Like many ‘new’ working class housing estates of the period (even when they offered greater standards of hygiene and comfort than the slums they replaced), Craigmillar was caught in the tension between the stated aspiration to build ‘homes fit for heroes’ and the reality of cost savings imposed by civic leaders that Swenarton has documented (1981).

Other silenced aspects of the mural subverted the ideology itself. The mural presents the area as a ‘new beginning’, a clean slate. Maxwell, unlike other muralists of the time such as Diego Rivera, chose not to represent what else existed in the area as a contrast to inner city slums besides fresh air, green open spaces and sunshine. The reality was somewhat different. Crummy (1992.p 28) makes no attempt to hide her watchmaker father’s political views, particularly towards the ruling aristocratic elite of the area. Furthermore, the estate was built on the land around and incorporating the mining and mill villages of Newcraighall, the Jewel and Niddrie. The majority of the men arriving in the area from across the UK and Europe in the agricultural depressions of the 1870-1910 and the post-World War 1 periods would find work in the newly expanding mining industry.

The ‘new’ residents were moving into spaces occupied by a number of differing communities. Each of these communities had their own ‘movement cultures’ (Michael Denning 1998 pp 67-77) based on collective actions, educational programmes and oral cultures. Examples range from the miners of the 19th century Newcraighall, and Jewel pits who supplied the coal to heat the houses of the city and later fire the new electricity-generating power station for the city at nearby Portobello in the 1920s, to seasonal agricultural workers and travelling people. Far from being a ‘new beginning’, old struggles re-appeared from a new place. Both industrialisation and innovation of the existing products of the area also took place bringing the factory system to bear on the production of coal, beer, bricks, margarine, biscuits and dairy produce.

_____________________________________________________

THE GENTLE GIANT AND THE GOLDEN 'M'

"I am for an art that comes out of a chimney like black hair and scatters in the sky".

- Claes Oldenburg 1961

"The (Craigmillar) community is at the leading edge of post-industrial innovation. It may seem paradoxical that in a multiply-deprived community the tide was turned by activities in the field of the arts. But paradoxes are apt to contain important meanings. Its most recent effort has been to bring forward the Craigmillar Comprehensive Plan for Action (Craigmillar Festival Society, 1978), which covers all aspects of community life and must now be negotiated with the various authorities concerned. How different it is from any document any planning department might have produced! It is an action plan to break the cycle of deprivation by those who have endured it."

- Professor Eric Trist 1979

_______________________________________________________

Standard writings on urban populations (particularly those who live on local authority housing estates) tend to stress the negative aspects of a limited social mix (Rogers and Power 2000). This discounts the possibility that the working class is not homogenous in its composition. In Craigmillar, the mix of former inner city dwellers (many of whom were immigrants from the Highlands, Ireland and central Europe with their own knowledges and skills) with industrial workers instead proved to be a potent brew in many ways.

The creative energy and organisational abilities of the area provided Edinburgh with its first Labour Party Lord Provost, Jack Kane.

There are also numerous examples of community action such as rent strikes, trade union campaigns, mothers unions and co-operative focused activity within the oral histories of the area. Craigmillar was not alone in this, as Worpole notes in his example of Silver End in Essex.

Yet the energies and creative dynamic of the people of Craigmillar extended beyond these forms of collective endeavour and also engaged with the educational and cultural fields.

Contemporaneously with the painting of the mural, Craigmillar is also notable in the siting and development of the Peoples College directly opposite the primary school. Founded by staff and students from the University of Edinburgh Settlement, the Peoples College focused on the human and educational development of non-school age residents.

Once again this development is linked to wider social and educational movements and discourses. The Peoples College was drawing upon not only the rich ideas and examples of the University Settlement movement, but also the Village Colleges of Howard Morris, the ‘Peoples Harvards’ in the USA (e.g. the New School for Social Research and City University in New York) and the Labour Colleges of John MacLean that were all active in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

There were also developments in cultural activity. The area had choirs, acting groups and craft activities. These were local examples of accepted cultural activities of the 1930s period. However, the versions of these in Craigmillar also drew heavily upon the cultural and political traditions and the ongoing local activities of the area from the mining community centred upon the Knlondyke and Jewel mines through to church based social activity.

As Helen Crummy has documented in her book, ‘Let the People Sing’ (1992), in the midst of material deprivation, the residents of the new estate simultaneously engaged with a wide-ranging mix of political, cultural and artistic discourses, influences and inspirations that were probably not foreseen by the city fathers who built the estate. Examples of this ranged from the aesthetics and ideologies of the modern movement in their local built environment, the mass cultures of radio, publishing and film, the culturally focused programmes of the Peoples College, the ‘movement cultures’ of the area and the political economy dominated curriculum of nearby Newbattle Abbey College which was part of the Scottish Labour College network.

Out of this mix over the period from 1940 to the early 1970s emerged a variety of collective interventions ranging from growth and development of local political organisations as described above to cultural agencies such as the Craigmillar Festival Society.

The area also produced a number of noteworthy cultural expressions and texts from residents of ‘Coketown’ such as the Bill Douglas film trilogy (1972-78), My Childhood, My Ain Folk, My Way Home that offer a radically different view growing up in a coalfield community.

Bill Douglas posters

Over the last four decades of the twentieth century, the Craigmillar Festival Society organised itself around the key issues for the local community such as unemployment, lack of education, arts, lack of space for children to play, youth, social welfare and the environment. These were explored using drama, carnival, festival, poetry, visual arts, sculpture and musical theatre and achieved involvement and ownership by the local community in doing so.

Gulliver - the Gentle giant that shares and cares - a community playground

In 1978, the Craigmillar Festival Society produced the first ever community led regeneration plan, The Comprehensive Plan for Action. Using a photograph of a local playground scupture of Gulliver, conceived by the sculptor Jimmy Boyle as the frontispiece, the document 'The Gentle giant that shares and cares' outlined a bold, imaginative community vision - a city of social justice

Consistent underlying themes and recommendations were the need for investment in people via jobs, education and amenities. Alongside these, there were aesthetic and moral challenges to pre-conceived notions as to the value and culture of local people in terms of their humanity. Again, Helen Crummy is quite explicit about this:

“Poverty is not only lack of an adequate income to live on, it is being classed as of little or no value to society, and as such, having one’s capacity for self-fulfilment crippled at birth”

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu sees such actions as signifiers of class conflict being contested within the cultural as well as the political fields and within specific historical and social settings. The experience of Craigmillar as a community developing a cultural focus and expression is in line with other examples from working class communities within the UK, such as Ashington in Northumberland with the work of the Ashington Group of miner painters who worked with the WEA and the work of the regional artist Tom McGuinness who worked as a miner all his life in the Durham coalfield.

Tom McGuinness - Gala Day

There is a considerable gap in the published research within the community development field and cultural planning field on the processes of cultural transmission. This suggests an interesting area of future research for cultural planners.

In the USA, the groundbreaking work of Michael Denning (1998) on the numerous workers cultural projects across the USA in the 1930s and 1940s begins to develop an analysis of the complex processes of cultural transmission from one generation to the next. Denning’s work also focuses on the expressions of class and racial struggle being carried out within the cultural field within this period. The signs of this struggle are contained in cultural documents ranging from small volumes of poetry and literature published by workers reading groups in the mid-west to the 1941 musical ‘Jump for Joy’ by Duke Ellington.

Drawing upon the analysis of cultural and social formations developed by Raymond Williams ( and also that of Gramsci, Denning focuses on the “structures of feeling” and “cultural formations” outlined by Williams:

“ One generation may train its successor, with reasonable success, in the social character of the general cultural pattern, but the new generation will have its own structure of feeling… the new generation responds in its own ways to the unique world it is inheriting.”

Williams also stresses that

“Cultural formations are simultaneously artistic forms and social locations”

Denning’s work on the cultural and social formations across the geography of the USA in the crisis of hegemony from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 until the post McCarthy era of the mid 1950s is instructive in both valuing and placing community based and working class focused cultural activities and interventions in both their immediate and historical context.

As he stresses many of these activities arose from the ‘structures of feelings’

“Of classes and peoples in transition: second generation workers caught between the immigrant cultures of their parents and the Americanist culture of high school, radio and the movies… for these young workers, culture itself was a labor, an act of self-enrichment and self-development."

And that this happened at a time when

“The very terms and values of cultural capital were in flux… and this created the space for both high culture popularizers, plebian avant gardes, and the arts that were not quite “legitimate” – jazz, cinema, photography, science fiction, detective stories and folk music”

(Michael Denning - The Cultural Front)

This flux in cultural capital both increased the sense of contest within the cultural politics of the period. Denning suggests that this took two forms: firstly in the critical attention paid by workers to the institutions and apparatuses of culture; and secondly as a politics of form in establishing canons of value that were oppositional to the dominant value systems.

I want to argue that the same processes and forms are present in Scotland and can be found in Craigmillar. In terms of the critical attention paid by workers to the institutions and apparatuses of culture, it is notable that the formation of the Craigmillar Festival Society in the late 1950s is closely related to the development of the Edinburgh Festival in 1947 and in many ways is a critical response to this.

Frontispiece of the Comprehensive Plan for Action (1978)

In terms of the development of a cultural politics of form that challenged dominant value systems, Further research is required to place these distinct artistic forms of resistance and alignment within their wider social formation. The plays, musicals, sculptures, photographs, musicals, poems and songs within the archives of the Craigmillar Festival Society alone represent a 'gold mine' of community cultural development. A personal retrospective of his own work by the artist Richard De Marco at Edinburgh’s City Art Centre (2001) was notable for the placing of the activities of the CFS within an artistic and social context of the last sixty years. This has been substantially added to by the 2004 exhibition "Craigmillar: Art the Catalyst"

In terms of defining a sense and a spirit of place as well as the multiple identities of a place these documents of the process and products of community development are of key importance to cultural planners. It can be argued that these are key research tools for cultural planners.

The history of the Craigmillar Festival Society and the many cultural texts and documents produced under its auspices from its foundation would also provide a matrix and an outline of the changes within the ‘structures of feelings’ within the Craigmillar community as different generations struggle to respond to the unique conditions they face.

These archives are fleeting and as people from the community die, or move out, the legacy of the Craigmillar Festival Society could be scattered to the wind. The gentle giant sculpture is presently in danger of demolition as part of the regeneration of the area.

On the site of the Klondyke mine, there is now a MacDonalds.

The sign of the Golden M

_________________________________________________________

WORK

THE OIL RUSH

___________________________________________________

CINDERELLA ROCKEFELLA

Yo-de-lady yo-de-lady that I love

(I’m de lady de lady who)

Yo-de-lady yo-de-lady that I love

(I’m de lady de lady who)

IS NOT FOR TURNING

Sir Denis sold the family business when he was in his 50s. Eventually, much later, he retired - but as divisional director of planning and control at the Burmah Oil Company, which had taken over Castrol, the company that had bought his family business.

_________________________________________________

THE OIL STORY - PART ONE

THE UPSTREAM

"After the nationalizations that swept the oil producing countries, beginning with Iraq’s nationalization in 1972, the oil multinationals lost much of their role in production, known in the oil business as “upstream.” Forced to abandon the cornucopia of profits in the Middle East (and to buy Middle East oil on the world market), they developed alternative production in such areas as the North Sea and the West Coast of Africa where production costs were higher and profits lower. They had to shift much of their profit-making to “downstream” activities such as transportation (tankers and pipelines), refining, petrochemicals and retailing. Major national oil companies (such as Kuwait and Venezuela) pursued downstream strategies as well, however, leading to overcapacity and falling rates of return.

To understand the special “national security” status enjoyed by the oil companies, we must first consider oil’s economic importance and then its central role in war. Oil provides nearly all the energy for transportation (cars, trucks, buses airplanes, and many railroad engines). Oil also has an important share of other energy inputs – it heats many buildings and fuels industrial and farm equipment, for example. Overall, oil has a 40% share in the US national energy budget. Beyond energy, oil provides lubrication and it is an essential feedstock for plastics, paint, fertilizers and pharmaceuticals. Sometime in the future, the world may switch to renewable energy and other non-oil inputs, but oil now reigns as the indispensable ingredient of the modern economy. For this reason, governments are nervous about their national oil supply"

- James Paul – Global Policy Forum

______________________________________________________

THE FIVE SISTERS

'IT'S SCOTLAND'S OIL' -

Political slogan of the Scottish National Party

In 1850, James Young, a chemist, discovered how to extract oil from shale coal. On the banks of the Forth, he created an industry that changed the world. He became known as 'Paraffin Young'. Oil from fossil fuels began to displace biological fuels such as whale oil for lighting and chemical processes. If you drive the A71 road from Edinburgh to Kilmarnock, you cut through this industrial area. There are chemical plants and the main hospital for skin burns and lesions is at Bangour. Near Addiewell, you can see the five huge red shale tips or 'bings' that were shaped and modelled on the 'Five Sisters' mountains near Kintail. They dominate the landscape of the plain.

August 1859

Edwin Drake drilled oil directly from beneath the surface of the earth to extract the 'black gold' directly.

The writing was on the wall for Paraffin Young.

The growth of the oil industry was rapid. John D. Rockefeller created the Standard Oil Company in 1870 and began to create 'Big Oil'. By the time of his death in 1937 at the age of 98, he was the richest man in the world. This was despite the Anti-Trust legislation against his Standard Oil, which meant that he had to break up the company into smaller off-shoots.

No matter. With his counterparts in Britain, Holland and France, these companies comprised the Seven Sisters (as christened by Italian oil tycoon Enrico Mattei) : Exxon (Esso), Shell, BP, Gulf, Texaco, Mobil, Socal (Chevron) -- plus an eighth, the Compagnie Francaise Des Pétroles (CFP-Total). In every family, there are deaths and shrinkages.

Now there are Five Sisters:

Exxon Mobil (Esso)

Shell

BP

Texaco,

Compagnie Francaise Des Pétroles (CFP-Total).

The Pool Association August 1928

The owners of the main oil companies met in Achnacarry Castle in Scotland to negotiate a trade agreement between themselves regarding the production and distribution of oil. Lengthy price wars and the threatening flow of Russian oil had drawn these men together to come to terms. They had two weeks of discussion and negotiation. This resulted in a seventeen page document that was known as the "Pool Association." Later it became known as the "As-Is" or " the Peace of Achnacarry ".

In 1974 the artist John Latham worked on the bings…

_____________________________________________________

THE OIL STORY - PART 2

THE DOWNSTREAM

Mossmorran is the site of a petrochemical processing plant on the north shore of the Forth.

Liquid gas is piped to Mossmorran from the North Sea, broken down to form ethane and then converted into ethylene. This is the basic hydrocarbon 'building block' of the petrochemical industry. Developed since 1985 by the Shell/Exxon partnership, the site's products are piped 3 miles (4.8 km) to the Braefoot Bay Marine Terminal and fed into tankers and gas carriers for markets in Europe and the USA.

Ethane and ethylene are also piped to the BP plant at Grangemouth on the South shore of the Firth of Forth and into the UK pipeline grid.

The original plant was built to handle liquids extracted from Shell/Exxon's Brent Field and other discoveries in North Sea waters east of Shetland. Later expansion equipped Mossmorran to handle hydrocarbons transported in pipelines serving fields in the central North Sea.

FORTH VALLEY - OIL CAPITAL

A survey in 1990 showed that the combined Mossmorran-Braefoot Bay facilities together injected more than £35 million a year into the Scottish economy.

At night you can see the fires.

_____________________________________________________

TRAIL 2 - THE GREAT ESTATES

_____________________________________________________

'One of the few ways of making sense of a period of sustained technological and social change is to start with family history'

- Chris Harvie - Peace and War in Steelopolis

____________________________________________________

THE OCTOPUS

When I was eight years old, my older sister and I went to the funfair in Portobello.

There was a ride there called the Octopus. It had eight arms, with cabins at the end of each arm, and it spun round like crazy. We went on. The operator shut the door on the cabin and it started up.

As it picked up speed and began to rise off the ground, the cabin door fell open. My sister and I hung on to the rail of the cabin for our lives. We were sure that at any second, we would lose our grip and be catapulted out in the Forth.

We screamed and shouted at the operator to stop the ride but he didn't. He gave us our full two minutes and eventually it stopped.

We shouted at the man and asked him why he had not stopped the ride?

didn't he know we could have been killed?

but he just shrugged his shoulders and said

"you get on for the ride of your life - and you don't get off"

______________________________________________________

FOLK

Fluid Identities in the deeps and shallows of time

"I've known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers " - Langston Hughes

My family are connected to the city of Edinburgh and the Forth river valley. Family members have made their homes here. My mother has lived most of her life in a fairly limited space in a two or three miles radius. My own homes have all been within a six-mile radius of the house I grew up in. If you want to think about it this way, we've been quite tied to place.

Many writers on people, place and identity have often struck me as being focused on the fixed elements of peoples' lives. The emotional ties to places expressed by the routines and the rites of passage such as birth, marriage and death. They focus their work on the timescale of the lifespan. As a result, the fluid elements of identity are less noted. The role of larger forces on lives are also barely touched upon. They ignore the moments of movement in a life. Instead, you get a focus on history that is only a bit of the picture. That misses the consistent but deep pulses in life.